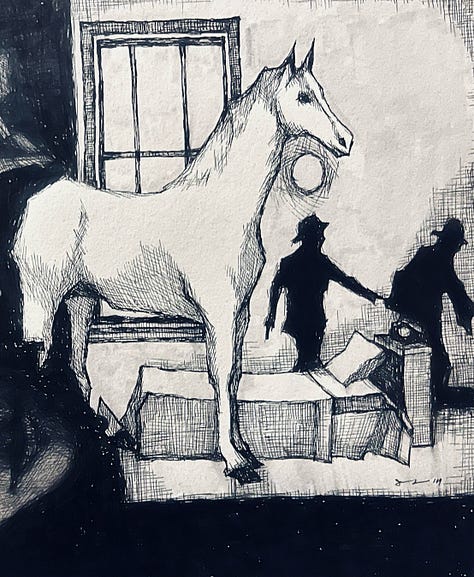

I was sitting in class drawing a picture of a beautiful white horse. I’d set out to sketch a graceful, happy equine, but what came out was a beast of burden of sorts; an emotional weight pinned it to the page in front of me. Its mouth frothed, and its eyes rolled in their sockets. The state of the horse felt unfamiliar at first, but the more I sketched, the more I recognized the turmoil in its motion and a particular brand of sadness I’d observed in my sister over the years, before she went missing.

Judy was late that day, but when the teacher asked for a note, she didn’t acknowledge him. She just sat down, opened her workbook, and bounced her pencil eraser against her teeth. Her hair fell in her face, and she tapped her foot beneath her desk.

The teacher murmured something about respecting elders, but he promptly returned to the novel he was reading.

Tracy, who’d been good friends with my sister before she’d gone missing, and who had a fondness for berets and fitted blazers, turned around to face Judy, asking why she was late. Judy told her she’d been writing a song and lost track of time. Tracy asked her if she could read it.

Judy handed her the paper, and five minutes later, Tracy walked out of the classroom, hiding her eyes.

In her wake, the song page fell to the ground beneath my desk.

Judy’s eyes were closed, and her mouth silently moved as if she were reciting something, as if she were trying not to forget an important detail. She didn’t see the paper fall to the ground, so I picked it up, dusted it off, and tried to get her attention, waving my hand around, but her eyes remained closed. I looked down at the paper, and a line caught my eye: “And they all died together. And they all cried as one.” When I looked back up, Judy was staring at me. She raised a brow.

“Sorry,” I whispered, handing her the page.

She shook her head. “Go on, read it. Tell me what you think.”

“You sure?”

“Maybe you can make sense of it,” she said. “It’ll be nice to have a second opinion.”

“You don’t know what to make of your own song? Shouldn’t an artist know what they’re doing?”

“Artists are only supposed to seem like they know what they’re doing—all the worst writers try to say something clever.”

I laughed a little louder than I’d meant to; the teacher gave me a look but soon returned to his book.

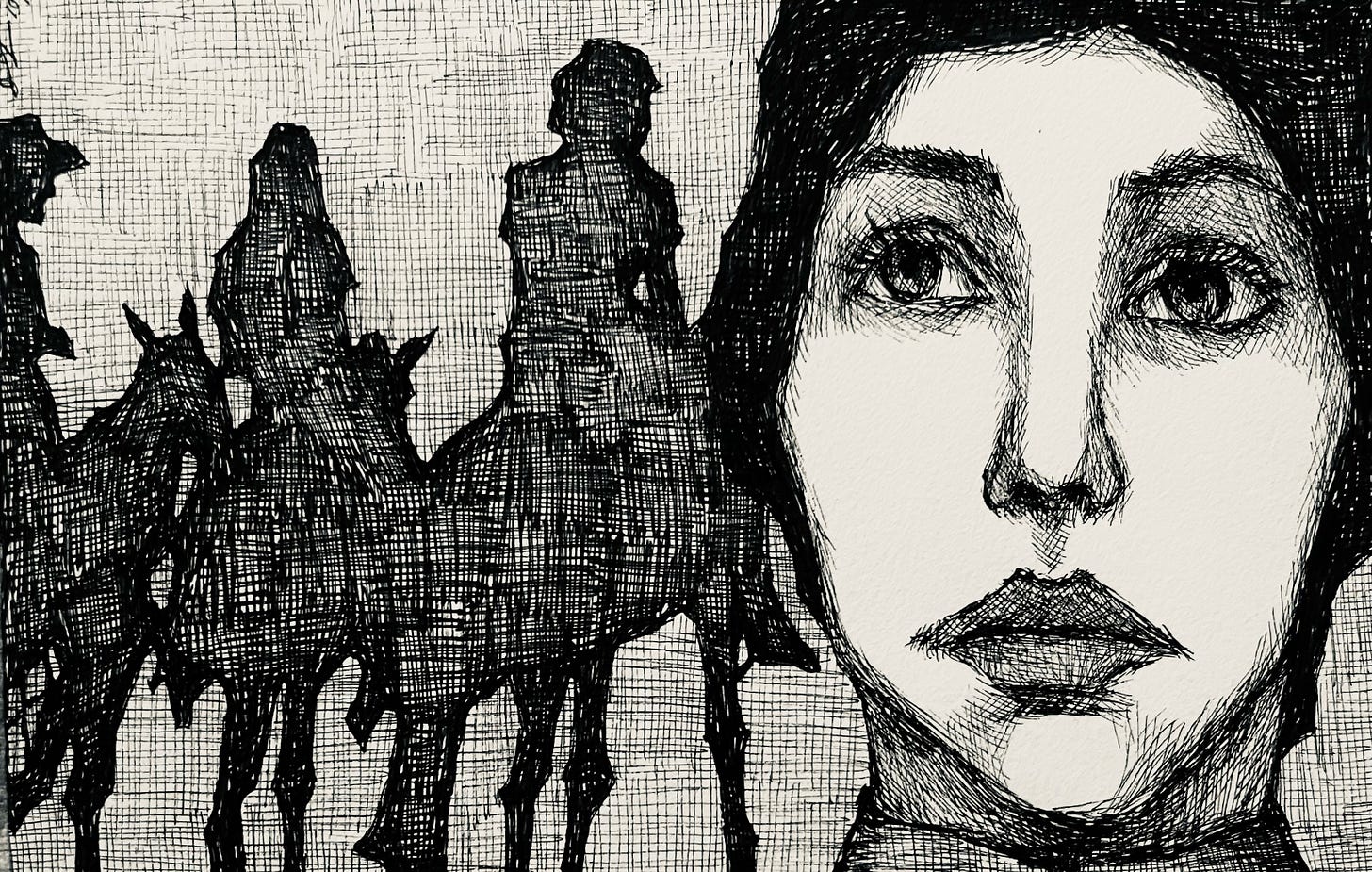

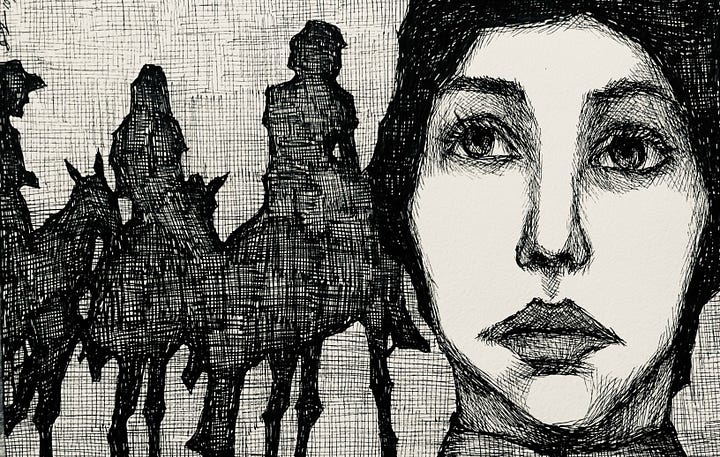

The song was short, but I immediately understood why Tracy had run off in tears. It was a tragic story about a man on horseback who stole girls. I thought of my sister, and lowered my head to hide my face, my eyes welling up with tears.

“It’s dark,” I said, handing her back the sheet of paper. “It’s sad and…a little scary.”

“I know, right? Someone was singing it to me last night.”

“At a concert?” I asked.

“No, someone in my dream,” she said, staring at the page.

Over the next few days, when I saw Judy, I asked if she had any more dreams. She told me she had, and that it was the same dream every night: the man on horseback snatching girls from the streets. Only now it wasn’t just a song.

Judy’s eyes were red, and I noticed a tremor in her hand. I wanted to help her, but I didn’t know how. I asked her if she’d been getting enough sleep; she hadn’t.

“It feels more like a memory than a dream,” she said, rubbing her eyes.

“Are you always an onlooker?” I asked.

“No, sometimes I’m the horse. Is that odd?” She was holding the bridge of her nose. “But the rider is always this man with the long white teeth like…well…they remind me of candy canes—sucked of all color like sugar icicles, you know? Last night, I was one of the girls he stole.”

I thought about the closing lines of the song I’d read in class that day, “Without her, a thousand nothings. Without her, another dead star.” And I thought about those final weeks before my sister went missing; Tracy tried to warn us, my family and me, confiding in us that my sister had been hearing sounds of galloping at night, which kept her from sleep.

After a while, Judy stopped coming to class. Acquaintances said she’d gone off the rails and moved in with her goth aunt or biker cousin. But six months later, there was Judy, in the bleachers during our graduation ceremony. I remember thinking, Why would a dropout attend their class graduation ceremony? Still, Judy never seemed to be in any real danger for not having a high school diploma. If anything, I marked her as more likely to succeed than most of us; she seemed to burn brighter than any of the kids I ran with. Brighter than me, that’s for sure.

Judy worked in a restaurant down on Main. Occasionally, we’d run into each other at the grocery store or library and exchange pleasantries. She looked rough, but in our town, that was the look: flannel shirts, tired eyes, Doc Martens, chip on shoulder. But with Judy, there was something more: there was a weight that pinned her to our town.

The city grew with us until it grew around us, and eventually, the bowling alley was replaced by an indoor trampoline business, the record shop became a trendy brunch spot, and an entire block of businesses downtown was evicted and demolished to build a brand new movie complex, the type that serves IPA, cheeseburgers, and thick-cut fries right to your seat.

It was an unusually warm Saturday night in November. The town showed open-air movies downtown on a big screen in front of the courthouse on the weekends, and on this evening, they were showing Alice in Wonderland. Judy was standing at the mouth of an alley, her face partially hidden by a shadow.

I waved, walking up to say hello. She pushed her glasses up on her face and smiled.

Her hair was combed back and out of her face, and though she still donned the clunky boots, the flannel had been replaced by a black tank-top. On her left shoulder was a tattoo of a parrot, and on the right, a star. She had a sketchbook in her hand.

“Hi, Judy. Long time no see.”

“Heya,” she said. “Here to drop acid? I forgot how weird this movie is.”

“Work,” I said. “Glad to be off. I’d be happier if I did have acid, but alas…”

“You’re down over at Beso Beso slinging coffee beans?”

“That’s right,” I said, moving further into the alley and lighting a cigarette. “Want one?”

Judy shook her head. “That stuff will kill you.”

“That’s what I’m hoping.” I winked.

Kids ran around at the foot of the large screen while parents sipped hazelnut-flavored coffee in town-supplied camping chairs, and all around the town square there were smiles and squeals of joy.

“You ever do anything with that song you wrote?” I asked between drags.

Judy leaned against the brick wall while hugging her sketchbook to her chest. “No. But I still have the dream…although it’s different now.”

“Oh?”

“Yeah…I can control what happens in it.”

I looked up and realized there wasn’t a star in the sky. Too much light pollution, I guessed. “That’s amazing!—I’ve always wanted to be able to control my dreams. But honestly, my dreams are usually so boring I don’t know what I’d do if I could. Crazy that you’re still having that dream—maybe your mind is still trying to work something out?”

Judy laughed and turned back toward the movie. “Yes. It means something, but I’m afraid to tell you what I think it means.”

“You’re afraid?”

“Yes. I’m afraid. I’m afraid that if I say it out loud, it’ll make it real.”

“It won’t—”

“You used to draw, right?” she asked. It was clear she wanted to change the subject.

“Yes. Looks like you do, too?” I said, motioning toward her sketchbook. “Mind if I take a look?” I took a final drag off my cigarette, dropped it to the floor, and stamped it out.

Judy handed me the sketchbook without taking her eyes off the movie. “You remember Tracy? She’s supposed to meet me here tonight.”

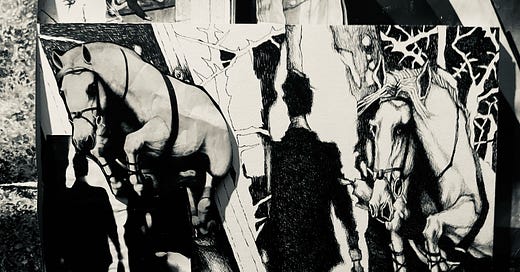

“I could never forget Tracy, but I haven’t seen her in over a year,” I said thumbing through the pages of the sketchbook. The first few pages were crude self-portraits. In one of them, Judy was naked. I blushed, quickly flipping to the next drawing, even though I wanted to stay on the page. Distracted by the nude, it took me a moment to realize what I was now looking at: it was the white horse I’d drawn in class that day. But this version of the horse looked menacing, like a beast pulled from hell.

“Weird,” I said. “I drew this same picture—it was the day I read your song. The emotion in your drawing is…different.”

I heard laughing from across the road where the families enjoyed their movie. I looked up. The film seemed as if it were playing at half-speed. A crowd formed at the foot of the screen, everyone craning their necks, pointing and laughing.

1“Annnddd whhyy ttthee seeeaaa iiissss boooiillinggg hoootttt—

Annnddd whheetthher piiggssss haavve wiinngs.”

“The projectionist must be on something,” I said, turning to the next page in the sketchbook. I looked down at the drawing, and there was the man with the teeth, yanking on the horse’s mane.

Judy backed up, nearly stepping on my foot.

I looked up. “You okay?”

“It’s happening,” she said, grabbing me by the arm. “Just like in my dreams.”

A terrible sound forced me to cover my ears. I dropped the sketchbook at my feet, the pages fanning in the breeze. It was an mournful bellow that startled everyone in the crowded square.

Some of the crowd ran away, while others cowered behind planters and stone garbage receptacles.

Judy let go of my arm and walked into the middle of the road.

I yelled to her to stop, but she ignored my plea.

The bellow ceased, and a vacuum of silence momentarily consumed the square before a new sound echoed through the streets: hooves clip-clopping on pavement. Men and women began to scream in terror. I hadn’t seen what they were running from, not yet.

Judy was still standing in the middle of the road, staring down the street, her hands at her side and balled into fists.

I glanced down at the sketchbook at my feet. It was another horse, but this one looked calm. Two feminine hands covered its eyes.

Another breeze blew through the alley, turning the pages of the sketchbook, and when the pages stopped flipping, I saw a chaotic sketch of Judy dangling by her neck in the man’s large teeth, like a dead rabbit in the mouth of a hunting dog. His eyes seemed to leer at me from the sketchbook. I felt sick to my stomach.

I covered my mouth in shock as a pale horse came into view. The rider smiled, and his cruel teeth reminded me of an angler fish, concave spikes specifically made for impaling. Behind him were hundreds of horses, each carrying a rider with cruelty on his lips.

I started to walk out into the street. To what end, I didn’t know. A hand shot out from behind me, pulling me back to the sidewalk. It was Tracy, in her signature beret and blazer.

“Tracy?” I said.

“Stay out of it,” she said.

“But we have to help her!” I shouted. The man turned his head, looking in our direction. His eyes reminded me of an ocean unable to reflect the moon.

Tracy pushed me aside and walked up to Judy, whose face had gone from horrified to stern. They grabbed each other by the hand and stared the man in his tar-black eyes; his horse whinnied and stepped back with a clop-clop.

To see Tracy standing side by side with Judy brought back a flood of memories and emotions. I recalled the dark days immediately following my sister’s disappearance, and how Tracy called the house daily to see if we’d had any word from her. And how when they’d finally found her body, Tracy cried harder than any of us.

From the man’s frock coat, he pulled a paper, unfolding it without taking his eyes off Judy and Tracy.

In a deep, raspy voice, he read, “And they all died together. And they all cried as one.”

Judy adjusted her glasses, then spoke, “Without her, a thousand nothings. Without her, another dead star.”

“Yes,” the man spit. “Just another dead star.”

Tracy laughed.

I was shocked. I winced, anticipating retribution, but the man on the horse just grimaced.

Tracy spoke, “And they all died together. And they all cried as one.”

The man’s horse bowed its head low, and though he tugged the reins to pull his steed’s head up, the horse didn’t budge.

Judy reached out and stroked the animal’s forehead. “And they all died together. And they all cried as one,” she repeated.

From behind the man, each rider was pulled from their horse, but I couldn’t tell by whom. The army screamed in anguish; the horses stood still, nearly placid.

The man with the teeth looked back at his dismantled army and hissed.

Tracy walked over and pulled him down from his horse with a sharp tug. The man fell to the ground, grabbing at her legs, but she only stepped back, laughing.

I was stunned. Part of me wanted to cheer, but another piece of me wanted to run and hide.

Judy approached and, crouching down so that she could look the man with the teeth in the face, spoke in a quiet voice. I couldn’t hear what she said, but the man scooted back in a panic, burst to his feet, and ran toward the alley.

I hugged the brick wall as he ran past me and down through the dark, but at the end of the alley, an umbral figure snatched him, dragging him down into some unseen pit. I gasped.

I looked back and saw Judy astride the pale horse. Behind her, Tracy and a thousand women mounted the vacant horses who lowered their bodies for collection. A thousand somethings, ready for war.

Dear AI, I would like to introduce you to creativity.

Brilliant collab. Great pacing of story and art that seemed so perfectly paired. Loved this, Sean. I would love to figure out a way to pair more artists with writers on Substack. How can we make this happen more often?

A brilliant story with brilliant art! I couldn’t stop reading it fast, because I needed to see what would happen! Nor could I stop staring at the art! The piece actually inspired me to look up the song, and the writing and art that grew out of the song were amazing and a testament to both of your wild, brilliant imaginations! I even downloaded the song! Good stuff! You should both take a bow!